The informal economy is a central pillar in the South African economy and a critical safety net for rural and urban communities alike. As town’s, countries and the world at large try to make sense of the massive social upheaval caused by Covid-19, the informal economy needs to be at the heart of our social, ecological and economic recovery efforts.

According to the International Labour Organisation, the informal sector is responsible for 85% of all livelihoods in Africa. In South Africa, it is estimated that the informal economy employs around 3.7 million people, accounting for one third of all jobs. In many parts of South Africa, the long-term trend sees the proportion of formal sector employment shrinking, while work in the informal sector is growing. A 2015 report by the Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council illustrates the increasingly central role of the informal sector in the region. They state that:

‘for every 100 people employed in the Eastern Cape’s formal sector in 1995, there were 14 fewer people in 2013. However, for every 100 people employed in the Eastern Cape’s informal sector in 1995, there were 64 additional people in 2013. This implies an employment shift from the formal economy to the informal economy; an inflow into the informal sector in the form of self-employment through the creation of micro-enterprises. This reality cannot be ignored.’

Therefore, as we consider recovery strategies, the need to ramp-up support for the informal economy in the wake of Covid-19 should be something which biosphere reserves take very seriously.

The question is how.

One point of entry for biosphere reserves could be through support for green-skills development.

To date, the informal economy has been almost entirely overlooked by the formal education system. But there is growing recognition for the need for serious investment into the knowledge needs of this vital sector.

Given, the relative success of the informal economy at creating and sustaining livelihoods for so many South African’s, we should be looking to understand and support existing approaches to learning within the sector, not trying to fit the informal economy into the rigid training models of formal training institutions. Research suggests that people in the informal economy tend to value short, problem orientated on-the-job learning because formalised courses designed ‘for’ rather than ‘by’ traders themselves often fail to provide the kinds of knowledge that those in the informal sector find useful in a format that is accessible. However, by the same token, many in the informal economy are held back by their lack of access to new knowledge. This is where the idea of learning networks can assist.

Learning networks are groups of people and organisations that come together on a voluntary basis with the purpose of mutual learning. In a learning network, people work as equals, collaboratively sharing ideas and information in order to further their knowledge about something that affects all the members.

Effective learning networks involve people from a wide range of backgrounds, who share common interests associated with a particular activity (such as agriculture, tourism, water management, fishing, or any other shared activity). Membership of such networks can include: formal and informal practitioners actively involved in the activity; trainers and educators who teach aspects of this activity; representatives of commercial organisations involved in this activity; representatives of NGOs, CBO’s and associations with interests in this activity, and; government officials mandated to support this activity. Within this context, the focus shifts from top-down training approach toward a longer-term process of collective problem solving and knowledge brokerage.

For example, in an agricultural learning network, a farmer may, from time to time, develop a new solution or new practice on their farm. However, it is often not the farmer themselves, but an extension worker, trainer or input salesperson within such a learning network who will help spread this new solution to farmers in other regions. The richer these networks of exchange and collaboration are, the more innovative and dynamic the network itself and the members become. In fact, a growing body of research now suggests that this kind of knowledge exchange is the starting point for innovation.

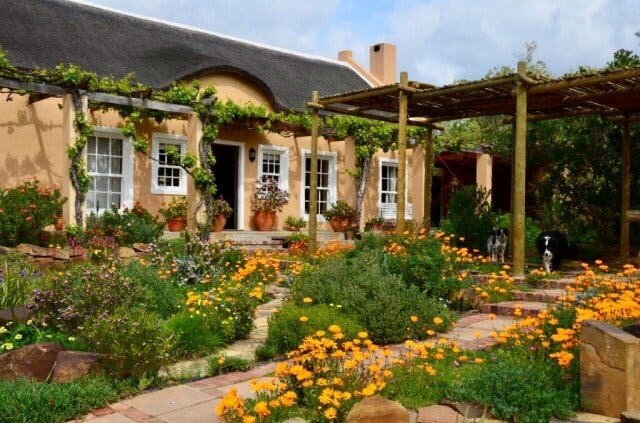

Figure 1: Farmers in a learning network come together behind a shed to share experiences around rainwater harvesting techniques on their farms

However, while learning networks have been shown to support inclusive and cost-effective learning in the informal economy, they do require some investment and coordination.

Given their historic function as boundary-crossing organisations that pull together different actors across a given region in support of harmonisation between man and biosphere, biosphere reserves have a unique set of relational skills, social networks, and green economy know-how. Unlike universities, colleges, and other traditional training institutions, which were set up to deliver training, biosphere reserves specialise in building and sustaining collaborative networks of relationship. These unique attributes could position biosphere reserves as ideal anchor institutions in the kinds of new learning networks needed to rebuild towards a greener and fairer economy from the ground up.

Dr Luke Metelerkamp is a research fellow at the Environmental Learning Research Centre at Rhodes University.

Those interested in setting up learning networks, might be interested in the following

stakeholder network mapping tool.

Cover photo credit: unsplash/Riccardo Annandale)